Women in Aviation: Past, Present and Future

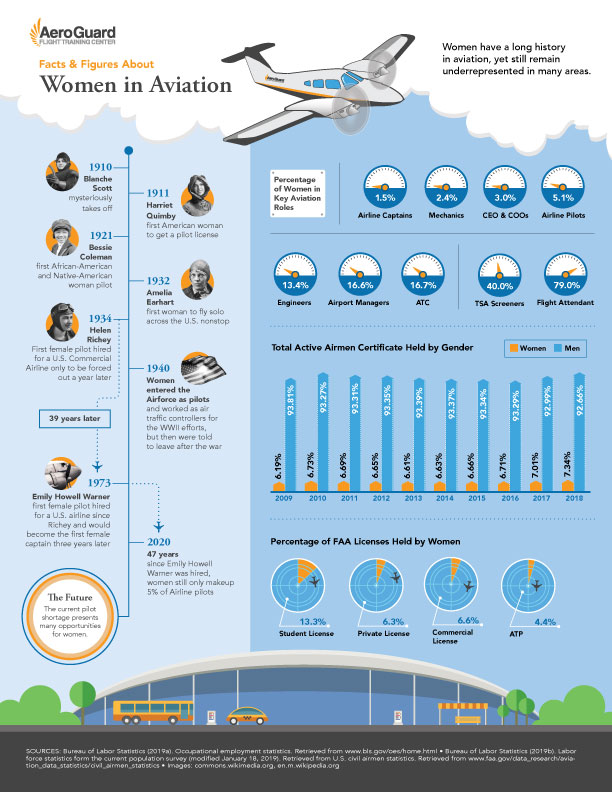

The next time you board a commercial plane, notice who your pilots are. It’s very likely the cockpit will seat two males, as they, without reason, make up 93% of all certified aviators.

In honor of the upcoming International Women in Aviation Conference, we’ll be examining the progression of women in aviation, from past to present and will also look at what we expect to see in the future.

Women have had a strong hand in the history of aviation but have experienced many setbacks along the way. However, with the pilot shortage, there has never been a better time to evaluate and work to correct the female underrepresentation.

Past: History of Women in Aviation

Women were responsible for many major milestones in the origins of aviation. They contributed to several “firsts” in the industry but faced constant prejudice.

One notable individual, Blanche Scott, not only became the first woman to drive across the U.S., but the first female pilot to fly in America. Her instructor, Glenn Curtiss, who was apathetic to give her flying lessons, inserted a block of wood beneath the aircraft’s throttle pedal so that Scott could learn to maneuver the plane, but only on the ground. During a lesson, the block “inexplicably” dislodged, sending Scott off on a short first “hop” of a flight, making history and demonstrating that women were perfectly capable of piloting an aircraft. She later joined Curtiss’ Exhibition Team, making her first official flight in 1910. She made a name for herself as “The Tomboy of the Air”.

Harriet Quimby, who wrote for a living, craved adventure. Covering aviation-related stories sparked her interest in the field. Knowing her intention to document her flight experiences, the magazine company she worked for paid for her flight lessons. As a result, Quimby received mail from the magazine’s readers who were fans of the “bird girl.” Excited for the opportunities aviation would bring her, Quimby studied hard. She was the first woman to receive a pilot’s license in the U.S. in 1911. The following year, she flew across the English Channel.

Bessie Coleman became first black female pilot and the first Native American woman pilot in 1922. Prior to her success as a pilot, her brother teased her about not being able to learn to fly, which only fueled Coleman’s desire to do so. Unfortunately, aviation programs in the U.S. denied her for being both African American and a woman. Keeping her head held high, she was eventually accepted into the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation in France, where women could learn to soar the skies. She took French classes as well to learn the language and prepare her for training. Coleman became known for her tricks and performance capabilities in the aircraft, proving her skeptics wrong.

Amelia Earhart, another powerful female aviator, found herself enthralled with the idea of flying at an early age. To prove her abilities and experience, she gave herself the pilot “look”, cutting her hair short and sleeping in her leather jacket to give it a worn appearance. Prior to her famous solo flight across the Atlantic in 1932, she also set a record, flying her own biplane 14,000 feet.

In 1934, Helen Richey was the first female pilot to be hired to fly by a commercial schedule passenger carrier. Due to gender discrimination and the angered male union formed at the airline, she was forced out in November of 1935.

Sabiha Gökçen was a Turkish aviator. She trained on fighter planes and bombers at an air base in Eskișehir, earning her title as the first female fighter pilot in the world in 1936. Gökçen flew with 22 different acrobatic and bomber aircraft throughout her life, receiving multiple medals that recognized her achievements.

The idea of female pilots especially became prominent during WWII.

The Women of WWII

In 1942, the U.S. dealt with a huge pilot shortage. To help fill the gap, women were trained to fly military planes, which in turn allowed men to be released for combat duty overseas. This elite group of female pilots were known as the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). As part of this Program, more than 1,100 women flew a variety of military aircraft. The Army Air Forces commanding general, Henry Arnold, at first unsure of the abilities of these women, went on to realize that women could fly just as well as men.

Unfortunately, the WASPs were disbanded in 1944, due to an increase of male pilot availability as well as political pressures. The women were told, “your volunteer services are no longer needed,” despite their immense efforts and contributions.

By the 1960s, there were 12,400 licensed women pilots in the United States, accounting for 3.6% of all pilots. This number doubled by the end of the decade to nearly 30,000 women but was still only 4.3% of total pilots.

Emily Howell Warner became America’s first female commercial airline captain, but that wasn’t until 1973. In fact, Warner was the first female pilot to be hired since Richey — 39 years of female aviator underrepresentation.

In the following years, these milestones continued, as Mary Barr became the first female pilot with the Forest Service, Captain Lynn Rippelmeyer became the first female to captain a 747 on a transatlantic flight in 1984 and Lt. Col. Eileen Marie Collins became the first woman pilot in the U.S. Space Shuttle program.

Even with all of these incredible stories, female pilots and women in aviation in general are still struggling to make a breakthrough in the industry present day.

Present: Women in Aviation Today

After all these years, the needle has hardly budged. According to Women in Aviation: A Workforce Report, a recent data collection by the University of Nebraska at Omaha Aviation Institute, women in aviation are underrepresented primarily in technical and leadership roles and overrepresented in low income, low profile positions. Of each of the areas of aviation, women make up…

- 1.5% of airline captains and 5.1% of all pilots

- 2.4% of mechanics

- 3% of CEOs, COOs, and other key leadership positions

- 16% of airport managers and air traffic control

- 40% of TSA screeners

- 79% of flight attendants

- 86% of travel agents

According to CNN, “women leave (the aviation industry) within five years because of lack of advancement or desire to achieve work-life balance, indicating this is a problem not just for the flight deck but for the entire aviation and aerospace industries.” However, “according to the study, women who leave aviation usually continue to work outside the home, indicating a lot can be done to retain women in aviation careers.”

The time is now to encourage women to pursue a career in the field, especially in lucrative leadership positions where gaps are the largest and ensure a work-life balance is obtained and maintained for the future.

Future: What’s Next for Women in Aviation?

In 2018, only 4% of those holding airline transport pilot (ATP) certificates (the certification needed to fly passengers and cargo as a professional pilot) were women. However, the Workforce Report also showed that over 13% of student pilots are women. From this information, we can infer that the number of women in the industry is growing and things are moving in the right direction. However, at 13%, despite more than tripling, women would still be hugely underrepresented.

It’s important to look at the pilot demand as an opportunity to fill the gap with more female pilots, as more than 800,000 new pilots will be needed, with more than 200,000 in the U.S. alone. There has never been a better time to pursue aviation. With continued efforts in education and outreach, we can expect to see more females in the cockpit and, feasibly, in other higher profile aviation roles as well.

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge